The High Seas Treaty: What , Who, and Why: Latest News

The High Seas Treaty officially entered into force this week, marking a major step toward protecting the parts of the ocean that lie beyond any country’s borders. Many people are asking simple, practical questions: What does this treaty actually do? Who enforces it? And how does it protect sharks, whales, and other wildlife?

The high seas are everything beyond 200 miles from any country’s coastline. No nation owns this space. For decades, it has been a place where illegal fishing, shark finning, and destructive practices could happen with almost no consequences.

What the Treaty Actually Does

It’s a global agreement where countries finally said they need rules to protect the parts of the ocean nobody owns. The treaty creates protected areas. Countries can now designate parts of high seas as no-fishing, no-mining, and no-drilling zone. It requires environmental checks, any major activity must be reviewed to ensure it won’t harm ecosystems.

It also increases transparency, ships must report what they’re doing instead of disappearing into the dark. The treaty also connects countries. Nations must share satellite tracking, vessel data, and enforcement actions.

What the Treaty Does NOT Do

It does not give countries ownership of the ocean. No one gains new territory or new rights. It does not control what countries do in their own waters. China, Korea, Japan, and others still control their own 200-mile zones.

Shark finning in those waters remains legal unless those nations choose to ban it. The treaty also does not create an ocean police force, this is no single global patrol boat.

So Who Enforces It?

Enforcement happens through existing systems that are now required to work together. Port countries: if a ship docks with illegal catch, the port can seize the catch, detain the vessel, fine the company, or ban it from returning. Flag countries: Every ship sails under a country’s flag. That country must investigate violations, punish illegal operators, and cooperate internationally.

There is also, Satellite monitoring: countries share tracking data, making it harder for illegal vessels to hide. Finally, there’s Coast guards and navies: they can board ships, inspect them, and take action when violations are suspected.

Why This Matters for the Ocean

Before this treaty, the high seas were a free-for-all. Now destructive fishing can be banned in protected zones. Migratory routes for sharks and whales can be legally protected. Illegal operators can be tracked, caught, and punished.

Countries must cooperate instead of looking the other way. It doesn’t fix everything, especially shark finning in national waters, but it closes the biggest loophole on Earth: the lawless two-thirds of the ocean.

The Bottom Line

The High Seas Treaty is the world finally agreeing to stop treating the open ocean like a dumping ground and start treating it like something bigger, more important, something worth protecting. Its not perfect, but it’s a turning point and a powerful start to 2026.

End of the Year: 2025 December’s Deep Sea Discoveries

Dark Oxygen: A New Source of Deep-Sea Oxygen Found 4,000 Meters Down

Scientists studying the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean have documented a phenomenon now called “dark oxygen,” where polymetallic nodules on the seafloor appear to generate oxygen in total darkness. The discovery began almost a year ago, when researchers repeatedly recorded unexpected oxygen spikes while sampling the seafloor at depths around 4,000 meters. With no sunlight at these depths, photosynthesis could not explain the readings.

In 2021 and 2022, scientists enclosed small areas of the seafloor inside experimental chambers to measure oxygen levels directly. Instead of the expected decline in oxygen caused by microbial consumption, the chambers showed rising oxygen levels. This suggested that something on the seafloor was producing oxygen in the absence of light. Suspecting polymetallic nodules was involved, these potato sized rocks contain manganese, nickel, cobalt, and other metals.

Laboratory tests showed that nodules can generate small electrical currents when placed in seawater like solutions. These currents may be strong enough to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen, acting like natural geobatteries. Measurements showed voltage readings ranging from a few millivolts up to 950 millivolts, approaching the threshold needed for water splitting. If confirmed, this process would represent a new light independent pathway for oxygen production on the seafloor. Scientists refer to this specific mechanism as nodule-associated dark oxygen production.

The implications extend beyond basic chemistry. Polymetallic nodules are central to ongoing debates about deep-sea mining. If these nodules play an active role in oxygen cycling, removing them could alter local biogeochemistry and affect deep sea ecosystems that rely on stable oxygen conditions. Researchers note that findings come at a critical moment as international regulations for mining in the Clarion Clipperton Zone are being developed.

Dark oxygen remains an active area of investigation, but the evidence so far suggests the deep ocean may host chemical processes that have gone unnoticed for decades. For ocean science, it adds another reminder that the seafloor is not a static environment. For conservation, it raises new questions about how industrial activity could affect systems we are only beginning to understand.

Iridogorgia Chewbacca a newly named deep-sea coral that is making headlines this month, not for size or age, but for its unusual appearance. In December 2025, researchers formally described Iridogorgia Chewbacca, a rare coral species whose long, glossy, hair-like branches resemble the silhouette of Chewbacca from Star Wars. The name is now official, but the species itself has been hiding in the deep for years. The first known specimen was photographed in 2006 during a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dive off Molokai, Hawaii, growing on a rocky slope thousands of feet below the surface. A second specimen was later collected in the Mariana Trench region, confirming that the species occupies some of the most remote and least-surveyed areas of the Pacific. These corals live in cold, dark waters where sunlight never reaches and temperature stay just above freezing. I. Chewbacca belongs to a family of deep-sea corals known for their tall, branching structures, but this species stands out. Its branches can reach up to 4ft in height, arranged in loose spirals that give the coral a shaggy, windswept look. Each branch is made up of hundreds of tiny polyps that function together as a single organism. Only two specimens have ever been collected, making it one of the rarest documented corals in its group. Corals like Chewbacca grow extremely slowly sometimes only millimeters per year which means individual colonies may be centuries old. Their presence can indicate long term stability in deep habitats, while their vulnerability highlights how easily these ecosystems can be damaged by deep-sea mining, trawling, or climate driven changes in ocean chemistry. Even with decades of ROV surveys, new species continue to appear in areas once thought barren. Iridogorgia Chewbacca may have earned attention because of its Hollywood nickname, but its scientific value is far more important. It represents another reminder that the deep ocean still holds species we’ve barely begun to study and the importance of protecting these habitats.

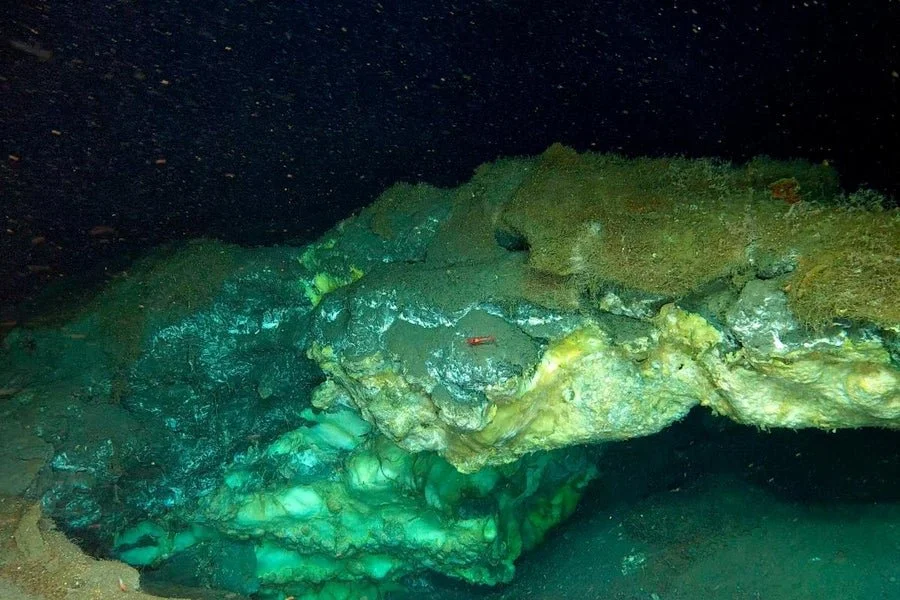

Scientists have documented the deepest gas hydrate cold seep ever found in the Artic, revealing a previously unknown ecosystem thriving 3,640 meters below the surface on the Molloy Ridge in the Greenland Sea. The site, called Freya Hydrate Mounds, was identified during the Ocean Census Artic Deep- EXTREME24 expedition and published in December 2025 in Nature Communications. This discovery pushes the known depth limit for gas hydrate outcrops nearly 1,800 meters deeper than any previously recorded site. Gas hydrates are ice like solids formed when methane and other gases freeze under high pressure and low temperature. They are usually found at depths shallower than 2,000 meters, so the Freya site shows they can form and remain stable in far more extreme environments than expected. The Freya mounds form a compact field of hydrate structures, collapse pits, and small ridges. ROV surveys documented active methane seepage, crude oil emissions, and a dynamic landscape where hydrate mounds appear to form, destabilize, and collapse over time. Researchers also recorded methane flares rising more than 3,300 meters through the water column, among the tallest ever observed globally. The gases at the site are thermogenic, originating from Miocene aged sediments. This indicates deep geological fluid migration over millions of years and shows that the system is shaped by tectonic activity, heat flow, and long-term environmental change. Despite the extreme depth and cold, the Freya site supports a dense chemosynthetic community. Observed species include siboglinid tubeworms, maldanid worms, snails, amphipods, and other seep associated organisms. Many of these species are also found at Artic hydrothermal vents, revealing an unexpected ecological connection between deep sea habitats once thought to be isolated from one another. Scientists say the Freya Hydrate Mounds provide an ultra deep natural laboratory for studying methane stability, deep carbon cycling, and how Artic ecosystems respond to environmental change. The findings also highlight the need to protect these habitats from future deep-sea mining or industrial activity, as they may play a critical role in the biodiversity of the deep Artic.

NASA and ESA Launch Sentinel-6B to Extend Global Sea-Level Records

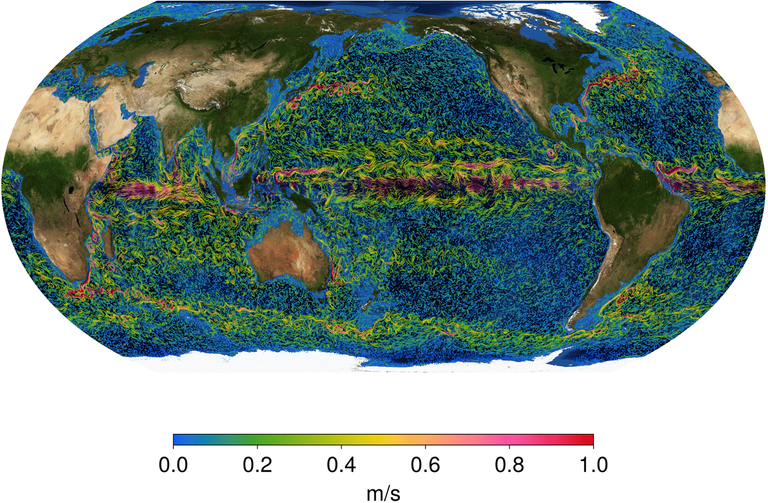

NASA and its European partners have launched Sentinel-6B, the newest satellite designed to monitor global sea levels with the high precision. The mission continues a decades-long effort to track ocean height, temperature, and circulation patterns from space. Sentinel-6B lifted off on November 16, 2025, and is now in orbit as the primary reference satellite for global sea-level measurements.

Sentinel-6B is part of the Copernicus Sentinel-6/Jason-CS mission, a collaboration between NASA, ESA, EUMETSAT, NOAA, the European Commission, and CNES. It succeeds its twin satellite, Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich, which launched in 2020. Together, the pair extend a sea-level record that began in 1992 with the TOPEX/Poseidon mission and continued through the Jason-1, Jason-2, and Jason-3 satellites.

The satellite carries a radar altimeter that sends signals to the ocean surface and measures the return time to calculate sea-surface height. It also includes an advanced microwave radiometer to correct for atmospheric water vapor, improving the accuracy of sea level measurements. Sentinel-6B will map about 90 percent of Earth’s ice-free oceans every 10 days, providing consistent global coverage.

In addition to sea-level monitoring, Sentinel-6B collects vertical profiles of atmospheric temperature and humidity using radio-occultation techniques. These data help improve weather forecasting, hurricane prediction, and climate modeling. NASA notes that the satellite’s measurements also support coastal planning, flood preparedness, and long-term climate assessments.

The mission is designed to operate through at least 2030. Its data will help scientists track how quickly oceans are rising, how heat is distributed across the planet, and how ocean circulation patterns are shifting. These long-term records are essential for understanding changes in coastal risk, storm intensity, and global climate trends.

Sentinel-6B’s launch marks the continuation of one of the most important climate-monitoring efforts in Earth science. With nearly four decades of continuous sea-level data, the mission provides a clear view of how the ocean is responding to warming temperatures and melting ice. The new satellite ensures that this record will remain uninterrupted for years to come.

Gold Rush, Holiday Gift from

the Ocean

December 2025 felt like the ocean was handing us gifts, a treasure hunt beneath the waves. Scientists announced the discovery of more than 866 new marine species, a surge so big it’s already being called an “Ocean Gold Rush.” From shadow reefs to the deepest trenches, the sea reminded us it still holds mysteries waiting to be uncovered - and that it’s still resilient enough to surprise us.

One of the discoveries that caught my attention came from Monzambique and Tanzania: the funky guitar shark. It looks like a mash-up between a ray and a shark, with a flat body and a tail that gives it a silhouette like a guitar. Only about 38 species of guitar sharks are known worldwide, and many are endangered, so seeing one thriving in these waters feels like hope. It’s a reminder that even the strangest shapes have a place in the ocean’s story.

The discoveries weren’t limited to one region. In the Red Sea, new reef species were cataloged, adding to the vibrant biodiversity of those warm waters. In the deep trenches, strange creatures like parasitic isopods and carnivorous bivalves turned up at depths of 6,000 to 8,000 meters. Altogether, expeditions spanned ten regions, from coral reefs to nearly 5,000 meters down, involving more than 800 scientists across 400 institutions. It was a global effort, and the results were staggering.

What struck me most is the reminder that the ocean isn’t just struggling under the weight of human impact - it’s still fighting to recover. Every new species discovered is proof that protecting marine ecosystems isn’t the only about saving what we already know. It’s about safeguarding what we haven’t even met yet. The guitar shark, the deep-sea snailfish, the countless tiny crustaceans - they’re all part of a living library we’re only beginning to read.

December’s discoveries show us that the ocean is still resilient, still mysterious, and still worth every ounce of protection we can give it. When humanity steps up - through treaties, bans on harmful plastics, or simply paying attention - the sea responds with resilience. That’s news worth celebrating, and it’s a story worth telling.

For me, this “Ocean Gold Rush” feels like a turning point. It’s not just about the numbers - 866 species, 10 regions, thousands of meters deep. It’s about the feeling that the ocean is still alive with possibility. And if we protect it, maybe we’ll keep discovering funky silhouettes like the guitar shark for generations to come.

Local Legend goes too soon, Remembering Jean Beasley….

Jean Beasley didn’t just protect sea turtles-she protected promises. After losing her daughter Karen to leukemia, Jean honored her final wish by founding a sea turtle rescue center on Topsail Island, North Carolina. What began as a small act of love grew into a sanctuary that healed thousands of turtles and inspired countless people. Jean’s hands were always busy-guiding hatchlings to the sea, comforting injured animals, and teaching children that every life, no matter how small, matters.

She believed conservation was about connection, not just care. Her impact is extraordinary. She founded the Karen Beasley Sea Turtle Rescue and Rehabilitation Center into a 13,000-square-foot hospital and education hub in Surf City. With more than 245,000 hatchlings safely reaching the ocean, and at least 1,600 turtles treated and released back into the wild. She was honored in 2022 with the Thomas L. Quay Wildlife Diversity Award for her long-standing leadership in conservation (North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, 2022).

Jean Beasley passed away in December 2025 at age 90, surrounded by loved ones. Her story is one of resilience, hope, and the power of turning personal loss into global impact. The center continues her mission, ensuring that her daughter’s wish lives on in every hatchling sprinting toward the waves.

Latest News: Great White Sharks on the Move

Latest News: Great White Sharks on the Move

This December has been full of activity for the Atlantic’s great white sharks. OCEARCH’s tracking program has reported several giants making their way south, covering thousands of miles and reminding us of the resilience of these Apex predators. Here are the latest updates on four extraordinary individuals.

Goodall at 13 feet long and weighing nearly 1,400 lbs. is a powerful female shark tagged off Nova Scotia in September. Since then, she has traveled more than 2,100 miles, recently pinging off Amelia Island and Jacksonville Beach in Florida. Named in honor of Dr. Jane Goodall, her journey highlights the importance of tracking technology in understanding how sharks migrate seasonally and adapt to changing waters.

Contender is one of the largest males ever tagged by OCEARCH, measuring almost 14 feet and weighing over 1,650 lbs. Earlier this month, he was detected off South Carolina, continuing his long journey southward. Since tagging, Contender has traveled nearly 5,000 miles, showing the incredible scale of these migrations. His size and stamina make him a standout in the program, offering scientists valuable data about how mature males use the Atlantic corridor.

Ripple is an 11-foot, 778-pound shark who has surfaced in Florida's Gulf waters. Tagged in Nova Scotia just months ago, he has already covered nearly 2,900 miles. His name reflects the idea that small ripples can grow into wave - a fitting symbol for conservation and awareness. Ripple’s movements through the Gulf remind us that younger sharks are just as vital to track, since their parents may reveal new feeding grounds and developmental stages.

Ernst is another impressive traveler, a 12-foot, 1,000-pound female who has pinged multiple times off Southwest Florida near Naples and the Everglades. Sine October, she has traveled more than 2,600 miles, zig-zagging through Gulf waters and demonstrating the wide range these sharks cover. Ernst’s journey underscores the important of protecting diverse habitats, from coastal shallows to deeper offshore zones.

Why These Updates Matter

These updates matter because together, these four sharks show the strength and adaptability of the species. Their migrations connect northern tagging sites in Nova Scotia with southern wintering grounds in Florida and the Gulf. By following their movements, scientists gain insight into feeding, breeding, and survival strategies.

The good news is that data suggests the Atlantic great white population is stable or even increasing - a hopeful sign for conservation. Each ping from Goodall, Contender, Ripple, and Ernst is more than just a dot on a map; it’s a reminder that protecting apex predators protects the entire ocean ecosystem.

Why Great Whites Matter to Me

For me, the great white is more than a headline or a tracking ping - it’s a symbol of resilience and restoration. These sharks embody the balance of the ocean, reminding us that protecting apex predators means protecting the entire web of life beneath the waves. Their journeys inspire my work with The Ripple Effect, showing how science and storytelling can spark care and action. Every time I share their updates, I hope readers feel the same awe I do - and recognize that safeguarding these giants is safeguarding our own future.

As these giants glide through Florida’s waters this winter, they carry stories of restoration and courage. Their journeys are living proof that when we care for the ocean, we create ripples of change that reach far beyond the waves.